Motivation

When you are developing a game for PC – or porting one – then you will have to deal with user input, generally from three distinct categories of sources: mouse, keyboard, and gamepads.

At first, it could reasonably be assumed that mouse and keyboard should be the simplest parts of this to deal with, but in reality, they are not – at least if we are talking about Windows. In fact, several extremely popular AAA games ship with severe mouse input issues when specific high-end mice are used, and some popular engines have issues that are still extant.

In this article we’ll explore a few reasons why that is the case, and end up with a solution that works but is still unsatisfactory. I assume that there is a whole other level of complexity involved in properly dealing with accessories like steering wheels, flight sticks, and so on in simulators, but so far I never had the pleasure of working on a game that required this, and this article will not cover those types of input devices.

If you are already an expert on game input on Windows, please skip directly to our current solution and tell us how to do it better, because I hope fervently that it’s not the best!

While the vast majority of this article is about mouse input, we also recently discovered something really interesting about xinput performance that we will share towards the end of the article.

Background – Raw Input

In Windows, there are many ways to receive input from the user. The most traditional one is to receive Windows messages, which are sent to your application’s message queue. This is how you receive keyboard and mouse input in a typical Windows application. However, this method has a few drawbacks when it comes to games.

The most notable of these drawbacks is that you cannot use the message queue to receive precise and unaltered mouse input, which is particularly important for any game where the mouse is used to control a 3D camera. Traditional input is meant to control a cursor, and the system will apply acceleration and other transformations to the input before it reaches your application, and also won’t give you sub-pixel precision.

If your game only has cursor-based input, e.g. a strategy game or point-and-click adventure, then you can probably get away with ignoring everything mouse-related in this article and just blissfully use standard Windows messages.

The solution to this problem is to use the Raw Input API, which allows you to receive input from devices like mice and keyboards in a raw, unaltered form. This is the API that most games use to receive input from the mouse, and the linked article provides a good overview of how to use it, which I will not repeat here.

So, why the somewhat whiny undertone of this article? Oh, we’re just getting started.

A Razer Viper mouse with 8k polling rate – I assume that all of these people stare in bewilderment as to why some of their games drop by 100 FPS when they use it (Image source: Razer)

A Razer Viper mouse with 8k polling rate – I assume that all of these people stare in bewilderment as to why some of their games drop by 100 FPS when they use it (Image source: Razer)

Using Raw Input

If you are familiar with the Raw Input API, or just read the linked documentation, then you might believe that I’m just getting at the importance of using buffered input rather than processing individual events, but really, that wouldn’t be too bad or worth an article. The real problem is that it is not nearly as simple as that – in fact, as far as I can tell, there is no good general way to do this at all.

Let’s step back a bit – for those who have not done this before, there are two ways to receive raw input from a device:

Using standard reads from the device, which is the most straightforward way to do it. This basically just involves receiving additional messages of type

WM_INPUTin your message queue, which you can then process.Using buffered reads, where you access all extant raw input events at once by calling

GetRawInputBuffer.

As you might surmise, the latter method is designed to be more performant, as message handling of individual events using the message queue is not particularly efficient.

Now, actually doing this, and doing it correctly, is not as easy as it should be – or maybe I just missed something. As far as I can tell, to prevent problems related to “losing” messages that occur at specific points in time, while only processing raw input in batched form, you need to do something like the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

processRawInput(); // this does the whole `GetRawInputBuffer` thing

// peek all messages *except* WM_INPUT

// except when we don't have focus, then we peek all messages so we wake up consistently

MSG msg{};

auto peekNotInput = [&] {

if(!g_window->hasFocus()) {

return PeekMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE);

}

auto ret = PeekMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, WM_INPUT-1, PM_REMOVE);

if (!ret) {

ret = PeekMessage(&msg, NULL, WM_INPUT+1, std::numeric_limits<UINT>::max(), PM_REMOVE);

}

return ret;

};

while (peekNotInput()) {

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessage(&msg);

}

runOneFrame(); // this is where the game logic is

As shown in the code snippet above, you need to peek all messages except WM_INPUT to ensure that you don’t lose any messages that occur between the times you are processing batched raw input and “normal” messages. This is not made particularly clear in the documentation, and it’s also not made particularly easy by the API, but a few extra lines of code can solve the problem.

All of this still wouldn’t be a big deal, just the normal amount of scuff you expect when working on an operating system which has a few decades of backwards compatibility to maintain. So, let’s get to the real problem.

The Real Problem

Let’s assume you did all this correctly, and are now receiving raw input from the mouse, in a buffered way, as suggested. You might think that you are done, but you are not. In fact, you are still just getting started.

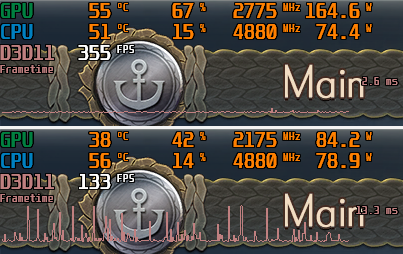

Comparison between no mouse movement (upper part) and mouse movement (lower part), everything else equal

Comparison between no mouse movement (upper part) and mouse movement (lower part), everything else equal

What you see above is a comparison of the frametime performance chart of a game, in the exact same scene. The only difference is that in the lower part, the mouse is being vigorously shaken about – and not just any mouse, but a high-end one with a polling rate of 8 kHz. As you can see, just moving the mouse around destroys performance, dropping from being consistently pegged at the soft FPS cap (around 360 FPS) to ~133 FPS and becoming completely unstable. Just by vigorous mouse movement.

Now you might think “Aha, he included this to show how important it is to use batched processing!”. Sadly not, what you see above is, in fact, the performance of the game when using batched raw input processing. Let’s talk about why this is the case, and what to do about it.

The Bane of Legacy Input

To make a long story short, the problem is so-called “legacy input”. When you initialize raw input for a device using RegisterRawInputDevices, you can specify the RIDEV_NOLEGACY flag. This flag prevents the system from generating “legacy” messages, such as WM_MOUSEMOVE. And there we have our problem: if you don’t specify this flag, then the system will generate both raw input messages and legacy messages, and the latter will still clutter your message queue.

So once again, why am I whining about this? Just disable legacy input, right? Indeed, that completely solves the performance issue – as long as you do everything else correctly as outlined above of course.

And then you congratulate yourself on a job well done, and move on to the next task. A few days later after the build is pushed to beta testers, you get a bug report that the game window can no longer be moved around. And then you realize that you just disabled the system’s ability to move the window around, because that is done using legacy input.

Disabling legacy input disables any form of input interaction that you would normally expect to be handled by the system.

So what can we do about this? Here is a short list of things I considered, or even fully implemented, and which either don’t work, can not actually be done, or are just silly in terms of complexity:

Use a separate message-only window and thread for input processing. This seemed like a good solution, so I went through the trouble of implementing it. It basically involves creating an entirely separate invisible window and registering raw input with it rather than the main window. A bit of a hassle, but it seemed like it would resolve the issue and do it “right”. No luck: the system will still generate high-frequency legacy messages for the main window, even if the raw input device is registered with the other window.

Raw input affects the entire process, even though the API takes a window handle.

Only disable legacy input in fullscreen modes. This would at least solve the problem for the vast majority of users, but it’s not possible, as far as I can tell. You seemingly cannot switch between legacy and raw input once you’ve enabled it. You might think

RIDEV_REMOVEwould help, but that completely removes all input that the device generates, including both legacy and raw input.You can’t switch between legacy and raw input once you’ve enabled it.

Use a separate process to provide raw input. This is a bit of a silly idea, but it’s one that I can think of that would actually work. You could create a separate process that provides raw input to the main process, and then use some form of IPC to communicate the input. This would be a massive hassle, and I really don’t want to support something like that, but I’m pretty sure it would work.

Disable legacy input, create your own legacy input events at low frequency. Another one in the category of “silly ideas that probably could work”, but there are a lot of legacy messages and this would be another support nightmare.

Move everything else out of the thread that does the main message queue processing. This is something I would probably try if I was doing greenfield development, but it’s a massive change to make to an existing codebase, as in our porting use case. And it would still mean that this one thread is spending tons of time uselessly going through input messages.

So option 1 and 2 would be somewhat viable, but the former doesn’t actually work, and the latter is not possible. The others are, in my opinion, too silly to explore for actually shipping a game, or infeasible for a porting project.

So perhaps now you can see both why there are AAA games shipping on PC which break with 8 kHz mice, and why I’m just a bit frustrated with the situation. So what are we actually doing?

Our Current Solution

Our current solution is very dumb and seems like it shouldn’t work, or at least have some severe repercussions, but so far it does seem to work fine and not have any issues. It’s a bit of a hack, but it’s the best we’ve got so far.

This solution involves keeping legacy input enabled, but using batched raw input for actual game input. And then the stupid trick: prevent performance collapse by just not processing more than N message queue events per frame.

We are currently working with N=5, but that’s a somewhat random choice. When I tried this I had a lot of concerns: what if tons of messages build up? What if the window becomes unresponsive? I didn’t worry about the game input itself, because we rapidly and with very low latency get all the buffered raw input events, but the window interactions might become unresponsive due to message buildup.

After quite a lot of testing with an 8 kHz mouse, none of that seems to happen, even if you really try to make it happen.

So, that’s where we are: an entirely unsatisfactory solution that seems to work fine, and provides 8k raw input without performance collapse and without affecting “legacy” windows interactions. If you know how to actually do this properly, please write a comment to this post, or failing that send an email, stop me in the street and tell me, or even send a carrier pigeon. I would be very grateful.

A Note on XInput

This is completely unrelated to the rest of the article, other than being about input, but I found it interesting and it might be new to some. When you use the XInput API to work with gamepads, you might think there is very little you can do wrong. It’s an exceedingly simple API, and mostly you just use XInputGetState. However, the documentation has this curious note, which is quite easy to miss:

For performance reasons, don’t call XInputGetState for an ‘empty’ user slot every frame. We recommend that you space out checks for new controllers every few seconds instead.

This is not an empty phrase: we have observed performance losses of 10-15% in extremely CPU-limited cases just by calling XInputGetState for all controllers every frame while none are connected!

I have no idea why the API would be designed like this, and not have some internal event-based tracking that makes calls for disconnected controller slots essentially free, but there you have it. You actually have to implement your own fallback mechanism to avoid this performance hit, since there’s no alternative API (at least in pure XInput) to tell you whether a controller is connected.

This is another area where an existing API is quite unsatisfactory – you generally want to avoid things that make every Nth frame take longer than the ones surrounding it, so you’d need to move all that to another thread. But it’s still much easier to deal with than the raw mouse input / high polling rate issue.

Conclusion

Game input in Windows ain’t great. I hope this article saves someone the time it took me to delve into this rabbit hole, and as I said above I’d love to hear from you if you know how to do this truly properly.

And we haven’t even gone into keyboard layouts yet! Are you a QWERTZ user and have you ever wondered why some games have default bindings that have actions on e.g. Z, X and C, which makes no sense on your input device? But that’s a story for another day.