Motivation

I’m a huge fan of local multiplayer, and in particular local cooperative multiplayer. I’m also interested in 3D rendering, and especially raytracing.

This blog post is the result of me finally – barely scraping into 2023 – writing about an idea I had in 2019, and which I implemented as a prototype in 2022. It uses the unique strengths of fully raytraced realtime rendering to implement a new kind of screen sharing for local multiplayer. But before that, some history.

If you’re not interested in the history lesson, then you can just skip directly to the result.

I swear that the history part is also interesting though!

Split-Screen and Shared-Screen History

One of the more significant challenges with implementing any kind of local coop is the fact that all players share a single screen. Ideally, a game can be designed in such a way to make use of one shared perspective, and I generally feel like these games work best for local multiplayer. But often, particularly for 3D games, working with a single perspective is not feasible.

Traditional Split-Screen Gameplay in Halo:Infinite

Traditional Split-Screen Gameplay in Halo:Infinite

The traditional solution to this conundrum is splitting the screen into N separate areas for N players, which are usually equally sized. Each shows a distinct perspective, and – in 3D rendering terms – has its own camera. Some games have developed this idea further, either visually or even by integrating it with gameplay. In the following I’ll go through a few examples of games that I am aware of which did something interesting within a single-screen, multi-camera framework.

Renegade Ops – Dynamic Splitting

The 2011 co-op twin-stick shooting action game Renegade Ops was the first time I encountered a system which varies the screen layout in multiplayer based on the relative position on the players in world space.

Renegade Ops’ Dynamic Split-Screen Implementation

Renegade Ops’ Dynamic Split-Screen Implementation

In the game, each player controls a vehicle, and when they are relatively close the screen is shared. If they move further away from each other, at some point the game switches over to two separate camera perspectives, which are split along a line that responds to the relative positioning. I.e. if the players were to be at the exact same postion on the horizontal axis, the line would be perfectly vertical, and if they were on the same vertical position, the split line would be perfectly horizontal. Any offset will result in a slanted line, as seen in the screenshot above.

Several more games with a top-down or isometric camera have had this type of dynamic visual style for split-screen since Renegade Ops. If you know of anything that does something similar earlier than it, do let us know.

In internal PH3 proofreading, it turned out that Lego Indiana Jones 2 used dynamic split-screen, and released in 2009. There might well be an even earlier example!

DYO – Splitscreen as a Gameplay Mechanic

DYO is an indie co-op puzzle platformer released in 2018. It implemented an idea which, to me, is nothing short of genius: instead of seeing the split-screen as a “necessary evil” required to allow two players with individual perspectives on a single screen, it instead re-conceptualized the split as a core gameplay mechanic.

DYO Uses its Split Screen as a Gameplay Mechanic

DYO Uses its Split Screen as a Gameplay Mechanic

In the game, players are given control over various aspects related to how and when the screen is split, and can e.g. arrange both halves to make a previously impassable obstacle traversable.

DYO is now free on Steam, so do check it out if this sounds at all interesting to you!

Degrees of Separation – Why Not Both?

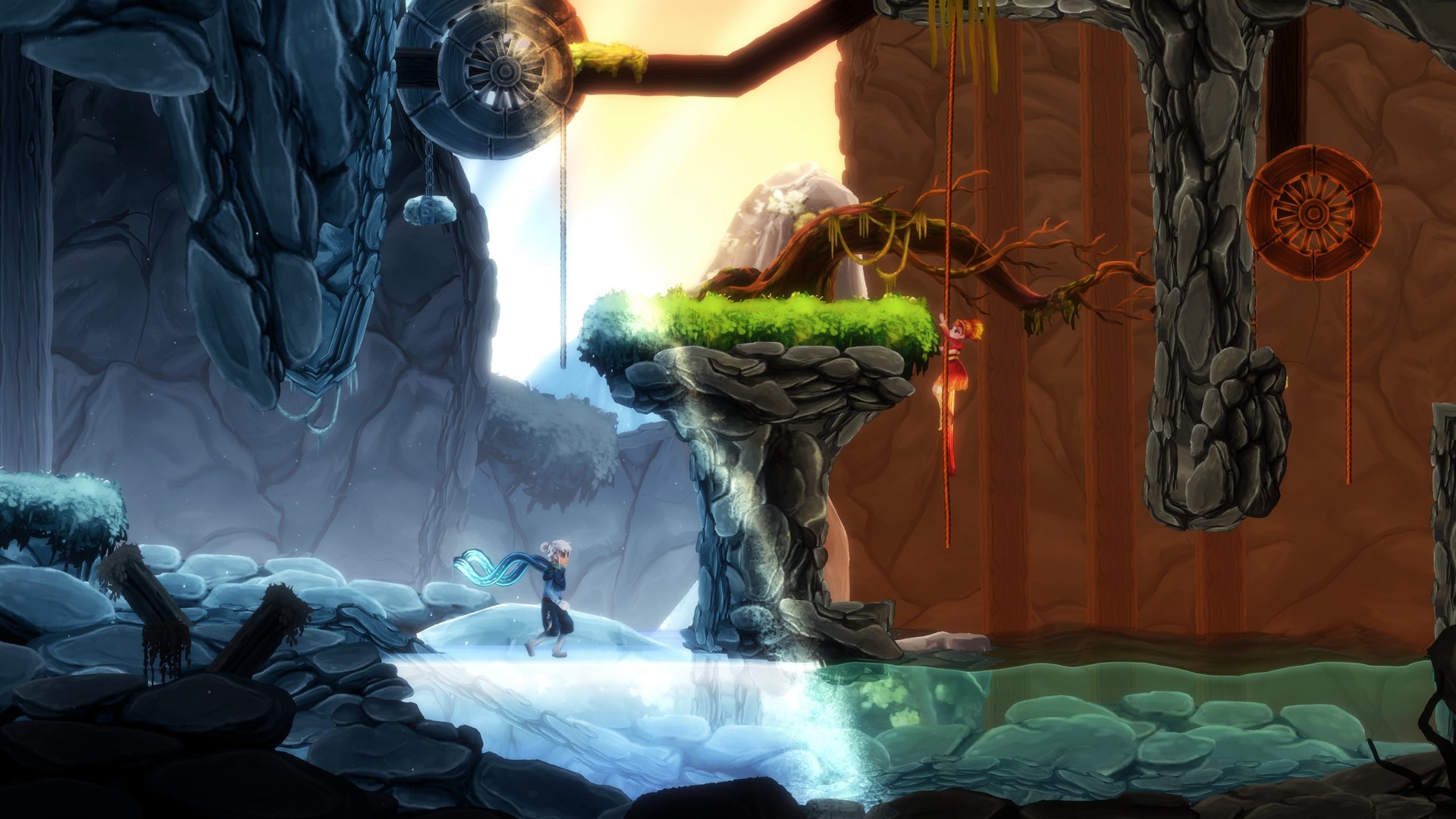

2019’s Degrees of Separation takes both Renegade Ops’ dynamic split and DYO’s screen-split-as-gameplay and integrates them into a brilliant puzzle platformer.

Degrees of Separation is Mechanically Interesting, and it’s also Beautiful

Degrees of Separation is Mechanically Interesting, and it’s also Beautiful

Each of Degrees of Separation’s levels introduces a new unique use of dynamic splitscreen as a mechanic, and each of those mechanics is in turn explored over many puzzles with quite some depth.

Ys IX – Just Don’t Split It

Overall, I’m not a huge fan of split screen gameplay, when it is not used in a really clever way as in the games above.

One option which I think is underutilized is simply not splitting the screen, even in fully 3D games. This is how the coop modes I implemented for both Ys VIII an Ys IX work. A single 3D camera does its best to keep both players in frame, and both players have the shared ability to adjust it. The video below some gameplay using that approach:

Of course, this is not without tradeoffs: even with quite a lot of time invested into tweaking the camera, it still takes getting used to and good coordination between both players, and there are situations in which it can fail to show one or even both actual player characters. However, I know that we and others fully completed these games, and the shared camera provides a unique gameplay feeling, so I wish someone else would also give it a try at some point.

You can read more about local coop in Ys IX in this Steam post announcing its release.

The Idea

There is one thing that all implementations of split screen gameplay I am aware of at this point have in common: regardless of how the screen is divided – either traditionally in a fixed distribution or dynamically – it is still ultimately just a split into two or more standard camera perspectives, with one alloted to each player.

Technical Background: Rasterization Limitations

This universal truth is not surprising. Realtime rendering in games – at least until the advent of HW-accelerated raytracing – was based on rasterization, and the traditional rasterization pipeline assumes that there is one consistent camera projection across the entire screen. In order to accomplish split screen rendering in 3D games, the traditional cross-platform approach required basically performing almost the entire work of rendering a frame again, once for each perspective.

A technology I’m also quite interested in, but which is unrelated to the topic of this post, actually brought some improvements in this respect: VR. VR rendering requires two perspectives, one per eye, or ideally even more for large-FoV displays. This motivated GPU vendors to provide improved support for this use case, though I am not sure if many (or any?) split-screen games actually leverage such hardware support.

NVidia has a thorough and very well-illustrated technical blog post about the VR-related multi-view rendering topic here. Give it a read if you want to learn more.

However, even with the most advanced hardware support, only up to 4 different views can be rendered at once without substantial performance implications – and even that requires quite a lot of development effort.

The Potential of Raytracing

Raytracing changes these fundamental rules, and essentially eliminates all of these limitations. Somewhat simplified, every pixel is generated by shooting an individual ray into the scene and seeing what it hits. As such, we can in theory use a different direction and position for every single one of these rays. And that’s where we can finally get to the idea this is all about:

Rather than having entirely distinct and clearly delineated perspectives for each player, dynamically adjust the camera(s) at a pixel level.

This allows us to not only use an arbitrary distribution of screen space to various players’ perspectives, but even smoothly interpolate between their perspectives!

Note that basically no mainstream game which uses raytracing today actually does so for the so-called primary or initial rays (mostly since rasterization is just more effective). It’s certainly possible to do so though, as you’ll see shorty.

The Result

Without further ado, here’s what that could look like:

This is a short video showing a basic implementation of this idea.

As you can see, the scene starts with a shared perspective, and when the two spheres (controlled by the two players) move further away from each other, the screen is smoothly split into separate areas for each of them. The most interesting part is what happens in the “no-man’s land” between, where space appears squished as the camera parameters are interpolated.

In case you’re wondering about the game: what you’re seeing (for the first time) is Sphere Spectacle. It’s something we worked on shortly after the release of the first RTX-series GPUs, so around 2019. The idea, at a gameplay level, is to basically be a ball-rolling game. At a technical level, we wanted to build something that is entirely raytraced, with absolutely no rasterization. We also didn’t want to use any images/textures at all in the game, so everything is just geometry and shaders.

Implementation

I won’t go into too much detail here, but the most interesting part of the implementation is how to actually decide to split the screen. I experimented with a few options here. Mathematically, the problem seems similar to trying to draw a Voronoi diagram with the players on-screen positions as the points, and then setting some value for the width of the interpolation. I tried making that work, but ended up reverting to a more ad-hoc solution.

What you saw in the video is the result of me trying a few different formulas and sticking with something that looks vaguely like what I wanted, but there is a wealth of options to explore here. I ultimately only spent two working days hacking this demo into Sphere Spectacle – and that includes implementing support for two players!

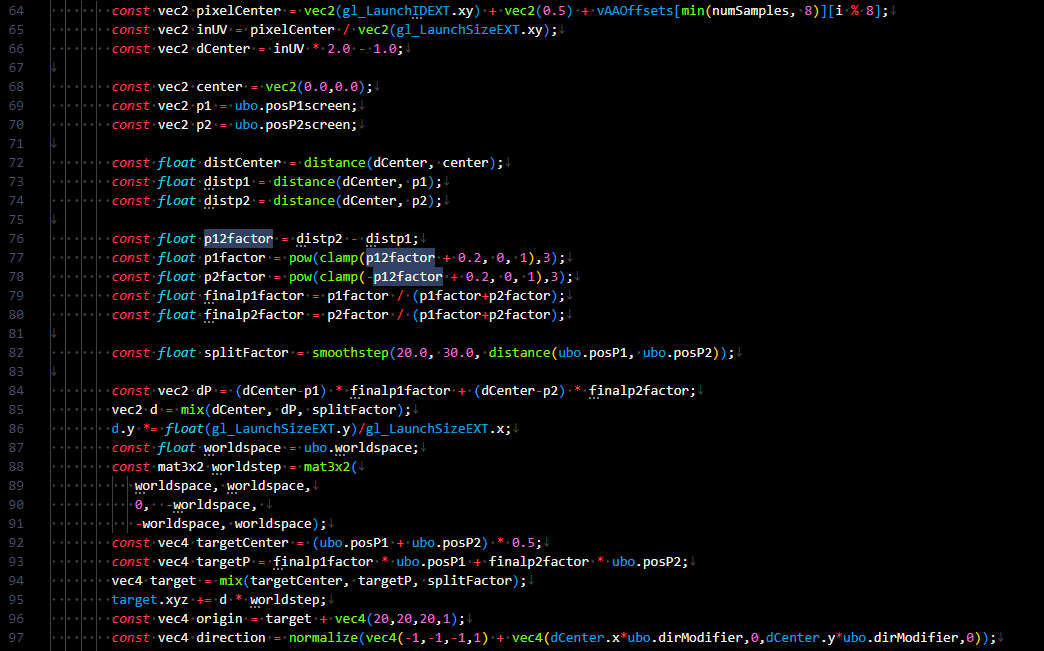

As one might expect from that, the code is quite unhinged. The most interesting core aspect is here, in this excerpt of the ray generation shader:

I still think it’s remarkable that I could get this entire idea working, at least to some extent, in just two days of hacking, and it shows how it is fundamentally so much simpler than trying to do anything like it in a rasterization pipeline.

Conclusion

If you’ve read until this point then thanks for coming with me on this journey through the history of local multiplayer camera perspectives and my idea on having it take a new step based on raytracing.

Now we just need someone to build a full game around it!