In a previous blog post we talked about how X macros can be leveraged to cut down on code repetition. We shortly described the concept of reflection and stated that, as of right now, C++ does not support reflection natively.

This series of blog posts explores an alternative to X macros, that is more reminiscent of reflection found in other programming languages. We use modern C++ features in combination with open-source libraries to build a non-trivial example. Through this process we aim to gain insight into the practicality of this approach.

But first, some background information and theory, followed by an overview of the example application.

Background

Reflection can be summarized as a mechanism that allows type information to be queried by the program. This type information contains, for instance, which fields and member functions are defined within a class.

If you haven’t already read the previous post about X macros, we recommend doing so before continuing with this one; if you are in a hurry, skim over the two sections The Problem and Meet Reflection.

Static vs. Dynamic Reflection

A reflection mechanism can typically be categorized as static reflection or dynamic reflection. Both categories have benefits and drawbacks that programmers should be aware of.

Dynamic Reflection (aka Runtime Reflection)

Dynamic reflection is generally more common and found in various high-level programming languages (e.g. Java, C#, Go). Here, type information is encoded into the binary in a way that it can be queried during runtime. This means that, during program execution, stored type information can be looked up and processed as needed.

This introduces some (minor) overhead compared to not using dynamic reflection and just writing the corresponding code manually (violating DRY). However, this mechanism allows the program to reflect upon types that didn’t exist during compilation. For instance, it’s possible to load a plugin dynamically and use reflection to gather information about a type defined within that plugin.

Another benefit of dynamic reflection is that it’s relatively easy to build a reflection mechanism yourself into a language that doesn’t already offer one. See RTTR and EnTT’s Meta for popular C++ implementations.

The main downside of dynamic reflection is that, since the reflection process happens while the program is executed, the compiler cannot catch any errors that aren’t immediately obvious to the type system. Therefore, rigorous testing is needed to ensure that any code using reflection is correct. Even further, dynamic reflection cannot be used at compile time — it is impossible to construct a new type based on reflection information.

Static Reflection (aka Compile-Time Reflection)

Static reflection happens during program compilation. The compiler records type information that can be queried during the compilation process. These queries are interpreted by the compiler, which uses the recorded type information to transform code into instructions specific to the corresponding types. The type information is not stored in the binary and cannot be queried during runtime. However, a static reflection mechanism can be used as basis for constructing a dynamic reflection mechanism.

Contrary to dynamic reflection, we cannot use static reflection on types that the compiler doesn’t know of. But, we do get the benefit of having compile-time checks, specifically type-checking for the generated instructions.

The X macros approach shown previously falls into this category.

Since static reflection requires the compiler to do the heavy lifting, a programmer cannot simply add a static reflection mechanism to their program — or can they? [Vsauce music starts playing]

Meet refl-cpp

refl-cpp is a library that uses modern C++ language features (e.g. constexpr) in combination with template metaprogramming to enable type-dependent, compile-time code generation. Let’s look at an example right away; the interested reader is encouraged to check out the official introduction.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

#include <iostream>

#include <refl.hpp>

namespace ikaros {

struct PostProcessParams {

float exposure = 1.0f;

float gamma = 2.2f;

int effectIndex = 0;

};

} // namespace ikaros

REFL_TYPE(ikaros::PostProcessParams)

REFL_FIELD(exposure)

REFL_FIELD(gamma)

REFL_FIELD(effectIndex)

REFL_END

namespace ikaros {

inline std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& out, const PostProcessParams& params)

{

auto members = refl::reflect<PostProcessParams>().members;

auto fields = filter(members, [](auto member) { return is_field(member); });

for_each(fields, [&](auto field) {

out << field.name << ": " << field(params) << "\n";

});

return out;

}

} // namespace ikaros

First we define the data type PostProcessParams and register it with refl-cpp. We need to tell refl-cpp which fields to consider for reflection. After that, we can obtain a list of fields and iterate over them using relf-cpp’s for_each utility. Combining field (a FieldDescriptor) with an instance of our type (params) allows us to read (and write) the corresponding field.

Taking a peek behind the curtain, the REFL_ macros are used to specialize the refl::reflect template for our type. For each field we list, a FieldDescriptor is constructed, which contains meta information and accessors for that field. These FieldDescriptors are then combined into a type_list. Since this information is stored within types and all of refl-cpp’s functions are constexpr, the loop inside our example can be unfolded completely during compilation.

This example uses Argument Dependent Lookup (ADL), which is a bit buggy in recent versions of Visual Studio. You might have to add the corresponding namespaces for this snippet to work.

Since C++ does not allow specialization of templates defined in an adjacent namespace, we need to invoke the

REFL_macros outside our project namespace.

Some people may be bothered by having to list fields again, after declaring the type. Unfortunately we don’t have a better solution for this at the moment. We recommend putting the

REFL_macros as close to the corresponding data type as possible.Also note that, since we are using static reflection, the compiler checks all of this. You may forget to register a field, but you cannot register a field that doesn’t exist.

This is just a tiny example — here’s a link to Compiler Explorer in case you want to play with it. refl-cpp provides many interesting features, some of which we use and explain in this series.

The Non-Trivial Example

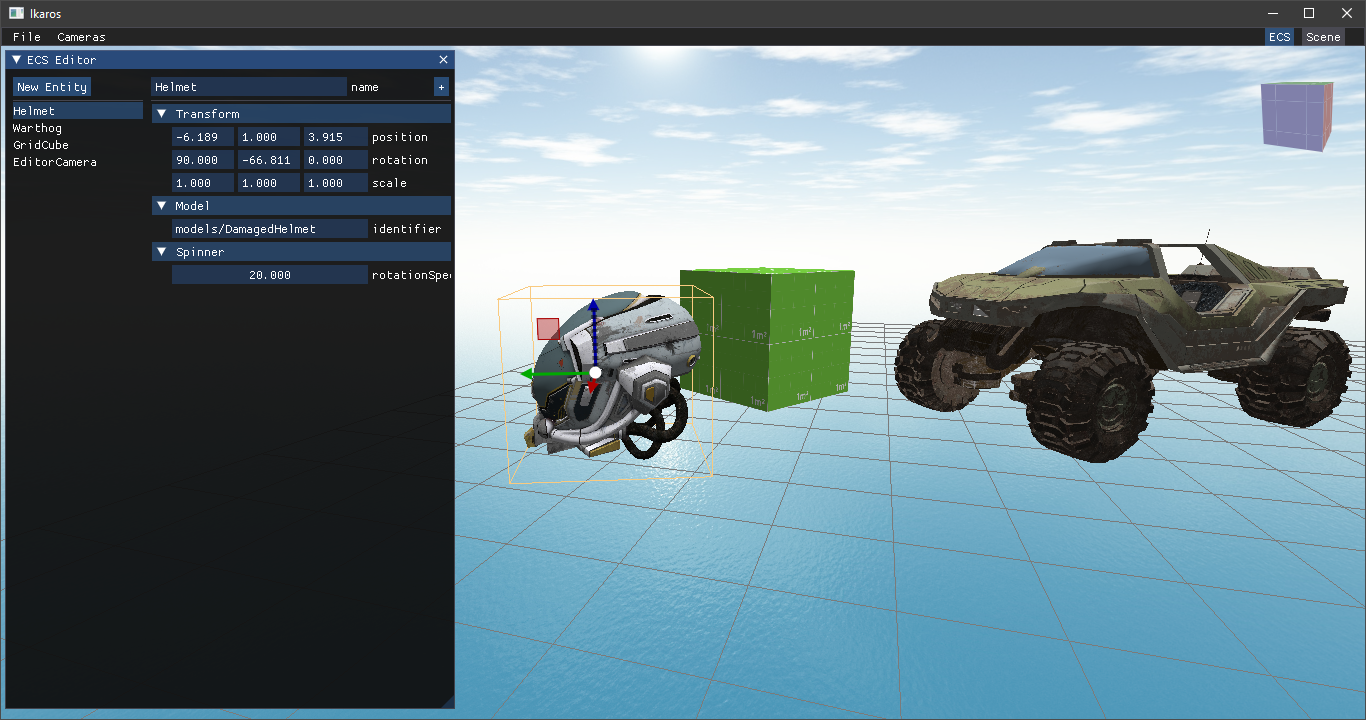

For the non-trivial example, we integrated this reflection mechanism into an internal research project — a tiny game engine prototype called Ikaros. Reflection is used for the editor, which allows developers to tweak properties of game objects in realtime. Furthermore, scene serialization and deserialization is also achieved via this reflection mechanism. While Ikaros isn’t open-source (yet), this series covers all the bits and pieces relevant for the reflection topic.

Internally, Ikaros uses:

- EnTT as Entity Component System (ECS) framework

- ImGui for the editor user interface

- GLM for math; and

- a few other utilities, like etl, RapidJSON, fmt …

This engine is an internal research project. The code shown in this series has not been battle tested and is therefore not supposed to be used in production!

About ECS

An Entity Components System architecture separates game objects’ state from their algorithms. State is organized into components, which ideally do not contain any logic themselves. The corresponding logic is realized as an (ideally stateless) system which operates on components. An entity represents a game object, but is semantically just a collection of components. The components associated with an entity determine the entity’s behavior.

For instance, a Transform component holds an entity’s position, rotation, and scale. If we now want to add a spinning behavior, where certain entities rotate around the up-axis over time, we define a SpinnerComponent and a SpinnerSystem.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

struct Transform {

glm::vec3 position;

glm::quat rotation;

glm::vec3 scale;

};

struct SpinnerComponent {

float rotationSpeed;

};

class SpinnerSystem {

public:

// Invoked every frame by the engine.

void tick(Scene& scene, float deltaTime) const

{

auto view = scene.registry.view<Transform, SpinnerComponent>();

for (auto [_, transform, spinner] : view.each()) {

glm::quat deltaRotation = glm::angleAxis(spinner.rotationSpeed * deltaTime, Vec3Up);

transform.rotation = deltaRotation * transform.rotation;

}

}

};

Neither Transform nor SpinnerComponent contain logic, while SpinnerSystem does not maintain state. scene.registry is the EnTT registry, which holds all entities and components of our scene. scene.registry.view allows us to iterate over all entities that have the given component(s) associated with it, here Transform and SpinnerComponent. Finally, we update the rotation using the current rotation speed.

In reality, components may provide some utility functions as well as maintain invariants.

Going into more details about ECS architecture and frameworks is beyond the scope of this series. If you want to know more, head on over to skypjack’s blog.

ECS Editor

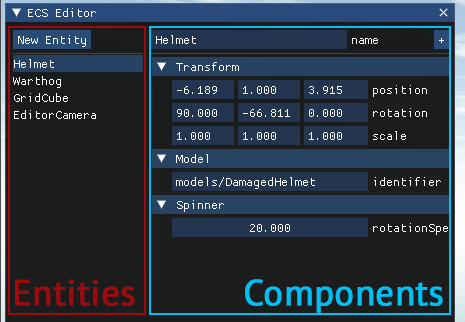

Inspecting and modifying entities and their components is an essential part of the realtime editor. The corresponding window consists of two parts. A list of entities present in the scene, on the left. And a list of components and their values for the currently selected entity, on the right.

We’ll construct this gradually over multiple steps. Here the first one, where we set up the basic layout and organization.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

class EcsEditor {

public:

void tick(Scene& scene)

{

ImGui::Begin("ECS Editor");

auto windowSize = ImGui::GetContentRegionAvail();

ImGui::BeginChild("Entities", {windowSize.x * 0.3f, windowSize.y});

scene.registry.each([&](entt::entity entity) {

bool isSelected = m_selectedEntity && m_selectedEntity == entity;

if (ImGui::Selectable(scene.entityLabel(entity).c_str(), isSelected)) {

m_selectedEntity = entity;

}

});

ImGui::EndChild();

ImGui::SameLine();

ImGui::BeginChild("Entity", {windowSize.x * 0.7f, windowSize.y});

if (m_selectedEntity) {

drawComponentEditor<Transform>("Transform", scene, *m_selectedEntity);

drawComponentEditor<ModelComponent>("Model", scene, *m_selectedEntity);

drawComponentEditor<SpinnerComponent>("Spinner", scene, *m_selectedEntity);

}

ImGui::EndChild();

ImGui::End();

}

private:

template <typename Component>

void drawComponentEditor(const char* componentName, Scene& scene, entt::entity entity) const

{

if (auto* component = scene.registry.try_get<Component>(entity)) {

if (ImGui::TreeNodeEx(componentName, ImGuiTreeNodeFlags_Framed)) {

EditWidgetDrawer drawEditWidget;

drawEditWidget(*component);

ImGui::TreePop();

}

}

}

std::optional<entt::entity> m_selectedEntity;

};

We iterate over all entities using scene.registry.each and create Selectable widgets for each one. Once such a widget is clicked, we store the current selection. While this looks pretty good already, there are issues with the second half.

EnTT does not provide a way to iterate over all components of an entity. Instead we have to list all components here, and check whether an entity has the corresponding component. If a new component is created by a developer, they have to update this list, otherwise the component won’t show up in the editor. This is suboptimal, but we can resolve this later.

Checking whether an entity has a specific component is usually a cheap operation. We don’t have to worry about the additional overhead here.

The other issue is EditWidgetDrawer used inside drawComponentEditor. We still don’t know what this is, so let’s cover this next.

EditWidgetDrawer

This brings us back on track with reflection. The purpose of EditWidgetDrawer is to draw the editing widgets for a given object — a component in this case.

Lets take the Transform component, register it for reflection, and look at EditWidgetDrawer’s implementation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

namespace ikaros {

struct Transform {

glm::vec3 position;

glm::quat rotation;

glm::vec3 scale;

};

} // namespace ikaros

REFL_TYPE(ikaros::Transform)

REFL_FIELD(position)

REFL_FIELD(rotation)

REFL_FIELD(scale)

REFL_END

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

class EditWidgetDrawer {

public:

bool field(const char* name, bool& value) { return ImGui::Checkbox(name, &value); }

bool field(const char* name, int& value) { return ImGui::DragInt(name, &value); }

bool field(const char* name, float& value) { return ImGui::DragFloat(name, &value); }

bool field(const char* name, glm::vec3& value) { return ImGui::InputFloat3(name, &value.x); }

bool field(const char* name, glm::quat& value)

{

// Display quaternion as euler angles.

glm::vec3 angles = glm::degrees(glm::eulerAngles(value));

if (ImGui::InputFloat3(label, &angles.x)) {

value = glm::quat(radians(angles));

return true;

}

return false;

}

template <typename T>

bool operator()(T& object)

{

bool changed = false;

if constexpr (refl::is_reflectable<T>()) {

auto members = refl::reflect<T>().members;

auto fields = filter(members, [](auto member) { return is_field(member); });

for_each(fields, [&](auto member) {

changed |= field(member.name.c_str(), member(object));

});

}

return changed;

}

private:

// Fallback to silently accept all types that are not drawable.

template <typename T>

bool field(const char*, T&) { return false; }

};

Handing an object to EditWidgetDrawer, we iterate over the registered fields and invoke the overloaded field member function. Since there may be fields for which we cannot draw a sensible edit widget, we added a generic fallback that doesn’t draw anything.

The boolean return types are not used yet, but they will come in handy later. Stay tuned!

Using the call operator as entry-point for this utility is not required. It’s just an aesthetic choice.

What’s Next?

In this first part we took a peek at refl-cpp and the underlying architecture of our running example. We then followed that up with the first iteration of the ECS editor feature.

In the upcoming parts, we’ll introduce the component registry which will resolve the outstanding issue of having to list all components explicitly in EcsEditor — and everywhere else where we would need to iterate over all components. Furthermore, we will see how additional information can be attached to reflected fields using attributes.